Description

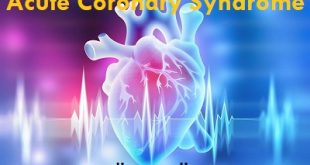

Acute cholecystitis is the most common complication of cholelithiasis. In fact, ≥ 95% of patients with acute cholecystitis have cholelithiasis. When a stone becomes impacted in the cystic duct and persistently obstructs it, acute inflammation results. Bile stasis triggers release of inflammatory enzymes (eg, phospholipase A, which converts lecithin to lysolecithin, which then may mediate inflammation).

The damaged mucosa secretes more fluid into the gallbladder lumen than it absorbs. The resulting distention further releases inflammatory mediators (eg, prostaglandins), worsening mucosal damage and causing ischemia, all of which perpetuate inflammation. Bacterial infection can supervene. The vicious circle of fluid secretion and inflammation, when unchecked, leads to necrosis and perforation.

If acute inflammation resolves then continues to recur, the gallbladder becomes fibrotic and contracted and does not concentrate bile or empty normally—features of chronic cholecystitis.

Pathogenesis of Acute Cholecystitis

The pathogenesis of acute cholecystitis is primarily due to obstruction of biliary outflow by a stone. Other rare causes may be stricture, kinking of the cystic duct, intussusception of a polyp, torsion of the gallbladder, pressure of an overlying lymph node on the cystic duct, or inspissated and concentrated bile. As the gallbladder distends following the obstruction, the blood vessels in the gallbladder wall become compressed, giving rise to a patch of gangrene on the fundus which can rupture and produce bile peritonitis. In addition to these mechanical and vascular factors various investigators have favored infection or chemical irritation as the cause of this disease.

What causes Acute Cholecystitis?

The causes of acute cholecystitis can be grouped into 2 main categories: calculous cholecystitis and acalculous cholecystitis.

Calculous cholecystitis

Calculous cholecystitis is the most common, and usually less serious, type of acute cholecystitis. It accounts for around 95% of all cases.

Calculous cholecystitis develops when the main opening to the gallbladder, the cystic duct, gets blocked by a gallstone or a substance known as biliary sludge.

Biliary sludge is a mixture of bile, a liquid produced by the liver that helps digest fats, and small cholesterol and salt crystals.

The blockage in the cystic duct causes bile to build up in the gallbladder, increasing the pressure inside it and causing it to become inflamed.

In around 1 in every 5 cases, the inflamed gallbladder also becomes infected by bacteria.

Acalculous cholecystitis

Acalculous cholecystitis is a less common, but usually more serious, type of acute cholecystitis.

It usually develops as a complication of a serious illness, infection or injury that damages the gallbladder.

Acalculous cholecystitis can be caused by accidental damage to the gallbladder during major surgery, serious injuries or burns, sepsis, severe malnutrition or HIV/AIDS.

Who is at risk to get Acute Cholecystitis?

You are at greater risk of developing acute cholecystitis if you:

- Have a family history of gallstones.

- Are a woman age 50 or older.

- Are a man or woman age 60 or older.

- Eat a diet high in fat and cholesterol.

- Are overweight or obese.

- Have diabetes.

- Are of Native American, Scandinavian or Hispanic descent.

- Are currently pregnant or have had several pregnancies.

- Are a woman who takes estrogen replacement therapy or birth control pills.

- Have lost weight rapidly.

What are the symptoms of Acute Cholecystitis?

The most common sign that you have acute cholecystitis is abdominal pain that lasts for several hours. This pain is usually in the middle or right side of your upper abdomen. It may also spread to your right shoulder or back.

Pain from acute cholecystitis can feel like sharp pain or dull cramps. It’s often described as excruciating.

Other symptoms include:

- Clay-colored stool

- Vomiting

- Nausea

- Fever

- Yellowing of your skin and the whites of your eyes

- Pain, typically after a meal

- Chills

- Abdominal bloating

Possible Complications

Untreated, cholecystitis may lead to any of the following health problems:

- Empyema (pus in the gallbladder)

- Gangrene

- Injury to the bile ducts draining the liver (may occur after gallbladder surgery)

- Pancreatitis

- Perforation

- Peritonitis (inflammation of the lining of the abdomen)

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Call your provider if you have:

- Severe belly pain that does not go away

- Symptoms of cholecystitis return

Diagnosis of Acute Cholecystitis

- Ultrasonography

- Cholescintigraphy if ultrasonography results are equivocal or if acalculous cholecystitis is suspected

Acute cholecystitis is suspected based on symptoms and signs.

Transabdominal ultrasonography is the best test to detect gallstones. The test may also elicit local abdominal tenderness over the gallbladder (ultrasonographic Murphy sign). Pericholecystic fluid or thickening of the gallbladder wall indicates acute inflammation.

Cholescintigraphy is useful when results are equivocal; failure of the radionuclide to fill the gallbladder suggests an obstructed cystic duct (ie, an impacted stone). False-positive results may be due to the following:

- A critical illness

- Receiving total parenteral nutrition and no oral foods (because gallbladder stasis prevents filling)

- Severe liver disease (because the liver does not secrete the radionuclide)

- Previous sphincterotomy (which facilitates exit into the duodenum rather than the gallbladder)

Morphine provocation, which increases tone in the sphincter of Oddi and enhances filling, helps eliminate false-positive results.

Hepatobiliary nuclear imaging (HIDA scan): This is an imaging test that involves an injected radioactive substance. A gamma camera sees the radiation as it moves through the different tracts of the digestive system. If that substance doesn’t enter your gallbladder, then the healthcare provider knows the organ is blocked, indicating cholecystitis. This test can also detect the function of the gallbladder and its ability to eject the bile once stimulated. This is called the ejection fraction of the gallbladder, which is considered normal when it is above 30-35%.

Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP): This type of MRI shows details of your liver, gallbladder, bile ducts, structures and ducts of the pancreas as well. It can show gallstones, inflammation or blockage of the bile ducts and gallbladder and if there is any inflammation of the pancreas.

Abdominal Computed Tomography (CT Scan): This X-ray test shows details of your liver, gallbladder and bile ducts. It shows inflammation of the gallbladder.

Laboratory tests are done but are not diagnostic. Leukocytosis with a left shift is common. In uncomplicated acute cholecystitis, liver tests are normal or only slightly elevated. Mild cholestatic abnormalities (bilirubin up to 4 mg/dL and mildly elevated alkaline phosphatase) are common, probably indicating inflammatory mediators affecting the liver rather than mechanical obstruction. More marked increases, especially if lipase (amylase is less specific) is elevated > 3-fold, suggest bile duct obstruction. Passage of a stone through the biliary tract increases aminotransferases (alanine, aspartate).

Treating Acute Cholecystitis

If you are diagnosed with acute cholecystitis, you will probably need to be admitted to hospital for treatment.

Initial treatment

Initial treatment will usually involve:

- fasting (not eating or drinking) to take the strain off your gallbladder

- receiving fluids through a drip directly into a vein (intravenously) to prevent dehydration

- taking medication to relieve your pain

If you have a suspected infection, you will also be given antibiotics. These often need to be continued for up to a week, during which time you may need to stay in hospital or you may be able to go home.

With this initial treatment, any gallstones that may have caused the condition usually fall back into the gallbladder and the inflammation often settles down.

Surgery

In order to prevent acute cholecystitis recurring, and reduce your risk of developing potentially serious complications, the removal of your gallbladder will often be recommended at some point after the initial treatment. This type of surgery is known as a cholecystectomy.

Although uncommon, an alternative procedure called a percutaneous cholecystostomy may be carried out if you are too unwell to have surgery. This is where a needle is inserted through your abdomen to drain away the fluid that has built up in the gallbladder.

If you are fit enough to have surgery, your doctors will need to decide when the best time to remove your gallbladder may be. In some cases, you may need to have surgery immediately or in the next day or 2, while in other cases you may be advised to wait for the inflammation to fully resolve over the next few weeks.

Surgery can be carried out in two main ways:

- Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy– a type of keyhole surgery where the gallbladder is removed using special surgical instruments inserted through a number of small cuts (incisions) in your abdomen

- Open Cholecystectomy– where the gallbladder is removed through a single, larger incision in your abdomen

Although some people who have had their gallbladder removed have reported symptoms of bloating and diarrhoea after eating certain foods, you can lead a perfectly normal life without a gallbladder.

The organ can be useful but it’s not essential, as your liver will still produce bile to digest food.

How can acute cholecystitis be prevented?

You can reduce your risk of developing acute cholecystitis by:

- Eating a healthy diet: Choose to eat a healthy diet – one high in fruits, vegetables whole grains and healthy fats – such as the Mediterranean diet. Stay away from foods high in fat and cholesterol.

- Exercising: Exercise reduces cholesterol, and the lower the cholesterol level the lower the chance of getting gallstones.

- Losing weight slowly: If you are making efforts to lose weight, don’t lose more than one to two pounds a week. Rapid weight loss increases your risk for developing gallstones

Diseases Treatments Dictionary This is complete solution to read all diseases treatments Which covers Prevention, Causes, Symptoms, Medical Terms, Drugs, Prescription, Natural Remedies with cures and Treatments. Most of the common diseases were listed in names, split with categories.

Diseases Treatments Dictionary This is complete solution to read all diseases treatments Which covers Prevention, Causes, Symptoms, Medical Terms, Drugs, Prescription, Natural Remedies with cures and Treatments. Most of the common diseases were listed in names, split with categories.