Description

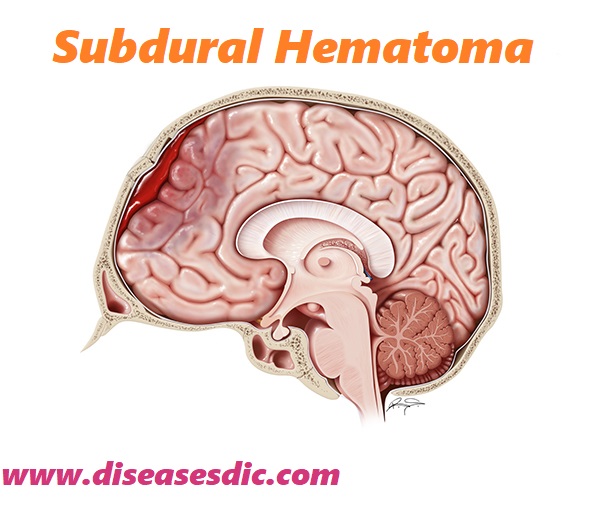

A subdural hematoma is the pooling of blood (hematoma) underneath the dura (subdural), the covering of the brain. This bleeding occurs when the blood vessels that bridge the subdural space, the area between the brain and the dura, are ruptured. The condition, if left untreated, can result in an increase in the intracranial pressure (ICP), which can put pressure on the brain and produce brain damage. The bleeding and increased pressure on the brain from a subdural hematoma can be life-threatening. Some subdural hematomas stop and resolve spontaneously; others require surgical drainage.

A subdural hematoma occurs not only in patients with a severe head injury but also in patients with less severe head injuries, particularly those who are elderly or who are receiving anticoagulants.

Different types of SDH

Subdural hematomas are named based on how fast they accumulate.

- Acute subdural hematomas usually appear within 72 hours of a traumatic event

- Subacute subdural hematomas are ones found within 3-7 days of an injury.

- Chronic subdural hematomas may take weeks to months to appear. These are more commonly seen in the elderly population where brain shrinkage stretches the blood vessels “bridging” between the skull and brain, making them more vulnerable. Brain shrinkage also creates more space within the skull, making the effects of blood accumulation slower to appear.

Pathophysiology

The usual mechanism that produces an acute subdural hematoma is a high-speed impact to the skull. This causes brain tissue to accelerate or decelerate relative to the fixed dural structures, tearing blood vessels.

Often, the torn blood vessel is a vein that connects the cortical surface of the brain to a dural sinus (termed a bridging vein). In elderly persons, the bridging veins may already be stretched because of brain atrophy (shrinkage that occurs with age).

Alternatively, a cortical vessel, either a vein or small artery, can be damaged by direct injury or laceration. An acute subdural hematoma due to a ruptured cortical artery may be associated with only minor head injury, possibly without an associated cerebral contusion. In one study, the ruptured cortical arteries were found to be located around the Sylvian fissure.

The head trauma may also cause associated brain hematomas or contusions, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and diffuse axonal injury. Secondary brain injuries may include edema, infarction, secondary hemorrhage, and brain herniation.

Typically, low-pressure venous bleeding from bridging veins dissects the arachnoid away from the dura, and the blood layers out along the cerebral convexity. Cerebral injury results from direct pressure increased intracranial pressure (ICP), or associated intraparenchymal insults.

In the subacute phase, the clotted blood liquefies. Occasionally, the cellular elements layer can appear on CT imaging as a hematocrit-like effect. In the chronic phase, cellular elements have disintegrated, and a collection of serous fluid remains in the subdural space. In rare cases, calcification develops.

Causes

The most common cause for a subdural hematoma is a head injury, such as from a car crash, fall, or violent attack. This sudden impact can strain the blood vessels within the dura, causing them to rip and bleed. Sometimes small arteries break within the subdural space as well. In some people, the brain shrinks (often from aging) and the subdural space gets bigger. This can make the blood vessels more likely to break. Possible causes for a subdural hematoma include:

- Head injury, such as from accidents or violence – most common among younger people

- Brain shrinking (atrophy) – more common among older adults

- Being on medicines to prevent blood clots, such as warfarin, aspirin, and other blood thinners

- Cerebrospinal fluid leaking

While rare, SDH’s can also appear without trauma. Abnormal blood vessels, dehydration, cancer, and blood clotting disorders have caused spontaneous SDH’s. Blood clotting medications, anabolic steroids used in bodybuilding, or cocaine use might also be factors.

Risk factors

People with the following conditions have an increased risk of having a subdural hematoma:

- Old age – this is the leading risk factor for having SDH’s

- Taking a daily aspirin or anticoagulation therapy

- Blood clotting disorder

- Alcohol abuse

- Frequent falls

- History of repeated head injuries

- Having an intracranial shunt

- Recent trauma

An increased risk of chronic subdural hematoma has also been linked with:

- Epilepsy – a condition that causes repeated fits (seizures)

- Haemophilia – a condition that stops your blood clotting properly

- Having a ventriculoperitoneal shunt – a thin tube implanted in the brain to drain away any excess fluid to treat hydrocephalus

- Brain aneurysms – a bulge in one of the brain’s blood vessels that can burst and cause bleeding on the brain

- Cancerous (malignant) brain tumors

Symptoms

Depending on the size of the hematoma and where it presses on the brain, any of the following symptoms may occur:

- Confused or slurred speech

- Problems with balance or walking

- A headache

- Lack of energy or confusion

- Seizures or loss of consciousness

- Nausea and vomiting

- Weakness or numbness

- Vision problems

In infants, symptoms may include:

- Bulging fontanelles (the soft spots of the baby’s skull)

- Separated sutures (the areas where growing skull bones join)

- Feeding problems

- Seizures

- High-pitched cry, irritability

- Increased head size (circumference)

- Increased sleepiness or lethargy

- Persistent vomiting

Complications

- Hematomas cause swelling and inflammation. Often the inflammation and swelling cause irritation of adjacent organs and tissues, and cause the symptoms and complications of a hematoma.

- One common complication of all hematomas is the risk of infection. While the hematoma is made of old blood, it has no blood supply itself and therefore is at risk for colonization with bacteria.

Diagnosis and Test

Diagnosing an intracranial hematoma can be difficult because people with a head injury can seem fine. However, doctors generally assume that a hemorrhage inside the skull is the cause of progressive loss of consciousness after a head injury until proved otherwise.

Imaging techniques are the best ways to determine the position and size of a hematoma. These include:

CT scan. This uses a sophisticated X-ray machine linked to a computer to produce detailed images of your brain. You lie still on a movable table that’s guided into what looks like a large doughnut where the images are taken. CT is the most commonly used imaging scan to diagnose intracranial hematomas.

MRI scan. This is done using a large magnet and radio waves to make computerized images. During an MRI scan, you lie on a movable table that’s guided into a tube. MRIs aren’t used as often as CT scans to diagnose intracranial hematomas because MRIs take longer to perform and aren’t as available.

Angiogram. If there is concern about a possible bulge in a blood vessel (an aneurysm) of the brain or other blood vessel problem, an angiogram might be necessary to provide more information. This test uses X-ray and a special dye to produce pictures of the blood flow in the blood vessels in the brain.

Treatments and Medications

Small subdural hematomas with mild symptoms may require no treatment beyond observation. Repeated head scans will likely be needed to monitor hematoma size and trends. Larger hematomas that produce increased pressure or brain shifting need urgent surgery for removal. There are three types of surgery used for removing hematomas. The technique chosen depends on clot size, location, and structure.

- Burr hole trephination is where surgeons drill a hole through the skull above the clot and wash it out with copious irrigation. This is most effective for removing liquefied hematomas. This method is common for Chronic SDH’s

- Craniotomy might be required for a larger and firmer clot. Here, a larger section of the skull is removed, the clot is lifted out, and the skull plate returned to its original position. This is the most frequent method for Acute SDH’s.

- Craniectomy is another procedure that removes a section of the skull, but with this method, the bone plate is left off for an extended period of time after clot removal. This method is less commonly used, mostly in cases where the underlying brain tissue has experienced major swelling.

Prevention

One of the ways to prevent a subdural hematoma is to protect yourself from head injuries by using proper safety equipment for work and recreation. Examples are hard hats, seat belts, and bike or motorcycle helmets. Older adults should be cautious and try to improve balance and avoid falls.

Take steps to protect young children from head injuries children by:

- Using properly fitted car seats

- Blocking stairways

- Bolting heavy furniture or appliances to the wall to avoid tipping

- Keeping children from climbing on unsteady objects

- Adding padding to countertops and sharp table edges