What is Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome?

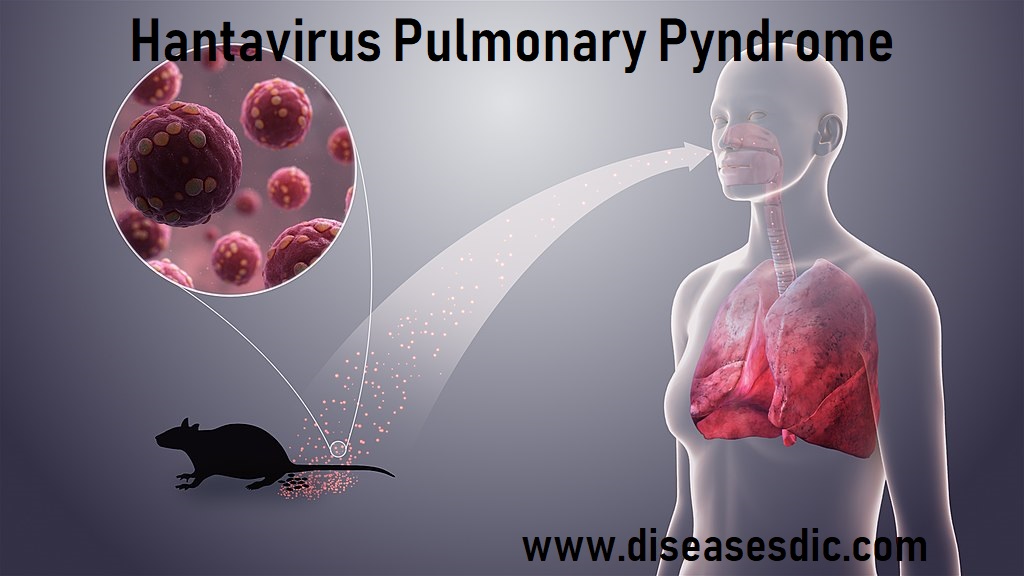

The term hantavirus represents several groups of RNA-containing viruses (that are members of the virus family of Bunyaviridae) that are carried by rodents and can cause severe respiratory infections termed hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) and hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (HFRS).

HPS is found mainly in the Americas (Canada, U.S., Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Panama, and others) while HFRS is found mainly in Russia, China, and Korea but may be found in Scandinavia and Western Europe and occasionally in other areas. Like HPS, HFRS results from Hantaviruses that are transmitted by rodent urine, rodent droppings, or saliva (rodent bite), by direct contact with the animals, or by aerosolized dust contaminated with rodent urine or feces to human skin breaks or to mucous membranes of the mouth, nose, or eyes. The vast majority of HPS and HFRS infections do not transfer from person to person.

The goal of this article is to discuss HPS; however, much of what is presented about HPS applies to HFRS – the main difference is that the predominant symptoms in the late stages of disease vary somewhat between the two diseases (lung fluid and shortness of breath in HPS and low blood pressure, fever, and kidney failure in HFRS). HPS is a disease caused by Hantavirus that results in human lungs filling with fluid (pulmonary edema) and causing death in about 38% of all infected patients.

Pathophysiology of HPS

The basic lesion of Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome is increased pulmonary capillary permeability that leads to severe pulmonary edema. The pathogenesis of pulmonary edema in Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome is not well understood, although an immunologic mechanism is considered to play an important role. The lymphoblasts and the macrophages recruited to pulmonary tissue by the high viral burden may provoke a lymphokine-mediated activation of vascular endothelium, thereby increasing pulmonary capillary permeability.

In 1999, Mori and colleagues used immunohistochemical staining to enumerate cytokine-producing cells (ie, monokines, such as interleukin [IL]-1α [IL-1α], IL-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α [TNF-α], and lymphokines, such as interferon-γ, IL-2, IL-4, and TNF-beta) in tissues obtained at autopsy from subjects with Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. [7] High numbers of cytokine-producing cells were observed in the lung and spleen tissues of patients with Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. These results suggest that local cytokine production may play an important role in the pathogenesis of Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome.

Patients with Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome have very high levels of viremia at the onset of pulmonary edema and then rapidly clear the virus from plasma; however, pulmonary damage persists. These data suggest that the endothelial cells are not directly injured by the cytopathic effect of viral infection.

What causes Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS)?

Hantavirus is caused by a group of viruses called Hantaviruses. Wild rodents such as mice and rats carry these viruses.

In most cases, people get HPS after inhaling particles of mouse droppings infected with these viruses. The deer mouse is the most common carrier of HPS.

The HPS virus can also spread to people after them:

- Are bitten by a rodent carrying the virus

- Touch a surface contaminated with rodent secretions (feces, urine, or saliva) and then touch their mouth or nose

- Eat food contaminated with infected rodent secretions

Risk factors of Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome

Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome is most common in rural areas of the western United States during the spring and summer months. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome also occurs in South America and Canada. Other Hantaviruses occur in Asia, where they cause kidney disorders rather than lung problems.

The chance of developing Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome is greater for people who work, live or play in spaces where rodents live. Factors and activities that increase the risk include:

- Opening and cleaning long unused buildings or sheds

- Housecleaning, particularly in attics or other low-traffic areas

- Having a home or workspace infested with rodents

- Having a job that involves exposure to rodents, such as construction, utility work, and pest control

- Camping, hiking or hunting

What Are the Symptoms of HPS?

HPS has three phases. The first phase is the “incubation” phase when the virus is inhaled into the lungs, ingested by immune cells, and then transported via the blood to other organs. This phase lasts for 2 to 3 weeks, and the patient has no symptoms.

The second phase lasts 2 to 8 days and includes rapid development of fever, dry cough, body aches, headaches, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Heart and lung failure can develop during this phase. Blood vessels become leaky and lead to the collection of fluid in the lungs, bleeding, and failure of the heart to pump. The combination of these changes leads to shock failure of several organs, and often death.

In the third phase, there are alternating periods of high and low urine production.

In the fourth and final phase, patients who remain alive have improving symptoms and recovery of organ function. Complete recovery occurs over several weeks. The symptoms of HPS seem to resolve as rapidly and dramatically as its onset.

Key symptoms and signs to watch for (especially with a history of rodent exposure) include:

- Fever greater than 101◦F, chills, body aches, headaches

- Nausea and vomiting and abdominal pain

- New rash (faint red spots)

- A dry cough followed by rapid onset of breathing difficulty

Complications of Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome

- Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome can quickly become life-threatening. As the lungs fill with fluid, breathing becomes more and more difficult.

- Blood pressure drops and organs begin to fail, particularly the heart.

- Depending on the Hantavirus strain, the mortality rate for the North American variety of Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome can be more than 30%.

Diagnosis of HPS

A positive serological test result, evidence of viral antigen in tissue by immunohistochemistry, or the presence of amplifiable viral RNA sequences in blood or tissue, with a compatible history of HPS, is considered diagnostic for HPS. Sin Nombre virus

Serologic assays

Tests based on specific viral antigens from SNV have since been developed and are now widely used for the routine diagnosis of HPS. CDC uses an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect IgM antibodies to SNV and to diagnose acute infections with other hantaviruses. Serologic confirmation of hantaviral infections has traditionally been done with neutralizing plaque assays, which have been recently described for SNV. However, these specific assays are also not commercially available.

Isolation

Isolation of hantaviruses (see below) from human sources is difficult, and the viruses causing HPS seem to be no exception to this rule. To date, no isolates of SNV-like viruses have been recovered from humans, and therefore virus isolation is not a consideration for diagnostic purposes.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC testing of formalin-fixed tissues with specific monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies can be used to detect Hantavirus antigens and has proven to be a sensitive method for laboratory confirmation of hantaviral infections. IHC has an important role in the diagnosis of HPS in patients from whom serum samples and frozen tissues are unavailable for diagnostic testing and in the retrospective assessment of disease prevalence in a defined geographic region.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

Reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) can be used to detect hantaviral RNA in fresh frozen lung tissue, blood clots, or nucleated blood cells. However, RT-PCR is very prone to cross-contamination and should be considered an experimental technique. Differences in viruses in the United States complicate the use and sensitivity of RT-PCR for the routine diagnosis of hantaviral infections.

What are the treatment options for Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome?

- There is no specific treatment for Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. It is important the infection is diagnosed early so patients can receive supportive care including oxygen therapy, fluid replacement, and blood pressure medications.

- Mechanical ventilation may be necessary for survival during the period of severe respiratory insufficiency.

- Excessive administration of fluids should be avoided despite the fact that patients may be hemoconcentrated and hypotensive. Overzealous fluid administration may aggravate respiratory insufficiency because of the increased vascular leak of fluid into the lungs.

- The early use of pressors is recommended to correct hypotension.

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation may be considered for patients with refractory shock. In one report, almost two-thirds of the patients with severe Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, with a predicted mortality of 100%, who were supported with extracorporeal circulation survived and completely recovered. However, the validity of this treatment is not well established through controlled trials.

- High-dose intravenous methylprednisolone for hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome was studied a double-blind, randomized controlled clinical trial in Chile. Although methylprednisolone appears to be safe, it did not provide any significant clinical benefit to patients.

- Treatment with intravenous ribavirin, a guanosine analog, conferred no survival benefit in an open-label trial. Hyperimmune serum offers a promising future therapy because survival is correlated with higher neutralizing antibody titers at admission.

How can HPS be prevented?

Keep your home clean to discourage rodents. Wash dishes promptly, clean counters and floors, put pet food and water away at night and store food and garbage in containers with tight lids. Prevent mice from entering your house by sealing all openings with caulking or steel wool. Remember, rodents can squeeze through holes as small as a dime.

Follow these precautions when removing a dead rodent or cleaning an area where rodents have been:

- Wear rubber, latex, vinyl or nitrile gloves.

- If you are going into a building, garage or basement that has been closed, open it to air out for at least 30 minutes before spending time inside.

- Wet down dusty areas that may be contaminated with rodent droppings or urine before cleaning them up. (You can use a commercial disinfectant or prepare a solution of 1 ½ cups bleach to 1 gallon of water.) Use a spray bottle to mist the area and gently but thoroughly wet it. A hard spray will stir up more dust.

- Wipe up debris; do not sweep or vacuum dry debris because it creates dust in the air.

- Dead rodents should be sprayed with disinfectant and then placed in a plastic bag containing enough disinfectant to thoroughly wet the carcasses.

- When cleanup is complete, seal the bag and place it into a second plastic bag. Then dispose of it by burying, burning or placing it in an appropriate waste disposal system.

- Before removing gloves, wash gloved hands in disinfectant and then in soap and water.

- Thoroughly wash hands with soap and water after removing gloves.

Control rodents outside your house:

Clear brush and grass away from the foundation.

- Place woodpiles and garbage cans on platforms at least 12 inches off the ground and keep them at least 100 feet from the house.

- Haul away junk that can provide homes for rodents.

When camping or sleeping outdoors, avoid disturbing or sleeping near rodent droppings or burrows.

- Avoid sleeping on bare ground. Use a mat or elevated cot if available.

- Store foods in rodent-proof containers and promptly discard, bury or burn all garbage.