Definition

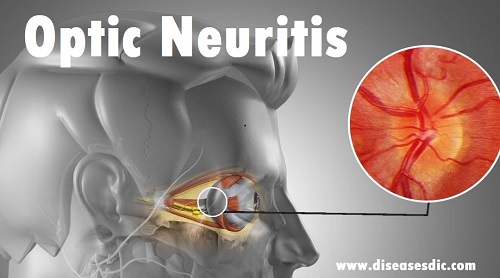

Optic neuritis is the inflammation of the optic nerve (the second cranial nerve). The inflammation causes a fairly rapid loss of vision in the affected eye, a new blind spot (a scotoma, usually in or near the center of the visual field), pain in the eyeball (often occurring with eye movement), abnormal color vision, and unusual flashes of light. The condition affects young to middle-aged people and affects women more often than men.

It carries visual data from the retina of the eye to a relay station in the center of the brain (the lateral geniculate nucleus) for transmission to a cortical area at the back of the brain (occipital lobes). Some instances of optic neuritis occur as a result of multiple sclerosis, a disease of unclear etiology that affects the optic nerve, brain, and spinal cord. Such individuals may or may not have a previous history of neurologic problems, and further testing is often performed to investigate the potential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis.

However, other manifestations of multiple sclerosis may not be fully evident until years after the onset of optic neuritis, if they occur at all. Other causes of optic neuritis include infections, such as Lyme disease or syphilis, as well as unknown causes, in which case the optic neuritis is termed idiopathic. Optic neuritis may be centered in the optic disk, the point of exit of the nerve from the eye (papillitis), or it may be in the nerve shaft behind the eyeball (retrobulbar neuritis). The optic nerve usually recovers from the inflammation, and vision gradually improves, but there often is residual degeneration of the nerve fibers and some persistence of visual symptoms. Repeated attacks of optic neuritis occur in some individuals.

Epidemiology

Optic Neuritis affects typically young adults ranging from 18 to 45 years of age, with an average age of 30 to 35 years. A strong female predominance is seen. The annual incidence is approximately 5/100,000, with a total prevalence estimated to be 115/100,000.

Optic neuritis pathophysiology

- The clinical course of demyelinating ON initially involves an episode of demyelination followed, in the majority of cases, by near-full recovery; recurrent attacks are also compatible with good visual function.

- However, a small group of patients will have a poor visual outcome after a single attack and progressive visual loss is seen in MS.

- The pathogenesis of demyelinating ON is thought to involve an inflammatory process that leads to activation of peripheral T-lymphocytes which cross the blood-brain barrier and cause a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction culminating in the axonal loss.

- Clinical recovery reflects the combined effects of demyelination with conduction block and axonal injury, on the one hand, remyelination with compensatory neuronal recruitment on the other.

- However, irreversible axonal damage occurs early in the disease process. A study using ocular coherence tomography (OCT) demonstrated that axonal injury is common in ON and observed retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thinning in 74% of individuals within 3 months of acute ON.

- In this and another cross-sectional study of MS patients with ON, RNFL was significantly reduced in the affected eye when compared with fellow eyes or disease-free controls. These and other studies have correlated RNFL thinning with impaired visual function.

- OCT can be employed to monitor such progressive axonal loss in both primary and secondary progressive MS.

Types of Optic neuritis

Optic Neuritis can come in the following types:

Demyelinating optic neuritis

Demyelinating optic neuritis is the most common form of the condition, and it occurs when the myelin coating found on your nerve fibers deteriorates, causing lesions to appear. These can prevent nerve signals from reaching your brain, which can affect your vision.

The cause of demyelination is not fully known; however, some evidence suggests that the breakdown of myelin is a result of the body’s own immune system. Demyelinating optic neuritis may not exhibit any symptoms, however if there are symptoms the condition is called acute demyelinating optic neuritis.

Retrobulbar optic neuritis

Retrobulbar optic neuritis is when the inflammation is on the back of the nerve behind the eye, which can make it painful to move your eye around.

Optic papillitis

Optic papillitis is when the head of the optic nerve is inflamed.

Risk factors

Risk factors for developing optic neuritis include:

Age: Optic neuritis most often affects adults ages 20 to 40.

Sex: Women are much more likely to develop optic neuritis than men are.

Race: Optic neuritis occurs more often in white people.

Genetic mutations: Certain genetic mutations might increase your risk of developing optic neuritis or multiple sclerosis.

Causes

It usually occurs in adults younger than 45 and affects more women than men. The condition is common in people who have multiple sclerosis (MS), which occurs when the body’s own immune system attacks and destroys protective nerve coverings.

Besides affecting eyesight, related nerve damage in MS can lead to loss of mobility and sensory functions, along with other debilitating conditions.

Other causes include:

- Infections such as toxoplasmosis

- Ocular herpes

- Other viral infections

- Sinusitis

- Neurological disorders

- Leber hereditary optic neuropathy, an inherited form of vision loss that affects mostly males in their 20s or 30s

- Nutritional deficiency

- Toxins, including alcohol and tobacco

During an eye exam, your eye doctor will look for signs of optic neuritis by conducting tests to evaluate whether you have reduced vision.

Your eye pressure will be measured, and your pupils will be dilated to provide a better view of the eye’s interior structures, including the optic nerve and retina.

When optic neuritis is present, the pupil always appears abnormal (afferent pupillary defect). This means the pupil actually dilates instead of constricting in the presence of bright light. Depending on the severity of optic neuritis, the optic nerve may appear normal or swollen.

If your optometrist or ophthalmologist suspects you have optic neuritis, a visual field test usually will be performed to determine if you have peripheral vision loss. You also might be referred to a specialty clinic to undergo an MRI of the brain to detect possible underlying causes of optic nerve inflammation.

A person with optic neuritis usually undergoes an MRI of the brain, to look for central nervous system lesions.

Optic neuritis symptoms

- It usually occurs in one eye, though occasionally both eyes are affected (about one in 10 times).

- Vision loss is common and typically occurs over a few days and stops progressing by one to two weeks.

- Symptoms include blurring of vision, a loss of part or all of central vision, reduced color vision, and dimness of vision.

- It may also be harder to see at night due to difficulty with contrast and glare.

- Most patients with ON have eye pain which is characteristically worse with movement of the eye.

- Sometimes people see flickering or flashing lights when they have optic neuritis (about 1 in 3 people).

- Some people notice that when they exercise or exert themselves their vision becomes blurrier.

Complications

Complications arising from optic neuritis may include:

Optic nerve damage: Most people have some permanent optic nerve damage after an episode of optic neuritis, but the damage might not cause symptoms.

Decreased visual acuity: Most people regain normal or near-normal vision within several months, but a partial loss of color discrimination might persist. For some people, vision loss persists after optic neuritis has improved.

Side effects of treatment: Steroid medications used to treat optic neuritis subdue your immune system, which causes your body to become more susceptible to infections. Other side effects include mood changes and weight gain.

Diagnosis and test

A doctor can diagnose optic neuritis with these tests:

- Thorough medical exam

- Evaluating your eyes’ response to direct bright light

- Testing of visual acuity using the letter chart to see how well you can see

- MRI scan of the brain

- Testing of the ability to differentiate color

- A complete examination of the back of the eye, known as the fundus

More testing may help to determine the underlying cause of optic neuritis. However, identifying a specific cause isn’t always possible.

Patient with optic nerve swelling from intracranial hypertension

Treatment and medications

Is optic neuritis permanent? In some cases, optic neuritis will get better on its own and no treatment (especially invasive treatments) will be necessary. But usually, the condition needs to be treated to manage symptoms and prevent inflammation or an infection from worsening. If someone has only had optic neuritis once- especially if they don’t have any other serious health conditions- they are likely to fully recover and restore their vision.

Conventional treatment typically includes:

The use of steroid medication called corticosteroids, which help to control swelling and usually improve vision. Steroids are typically injected into your numbed, affected eye so they can reach the optic nerve. Steroids have been shown to do little in terms of improving visual acuity in patients with optic neuritis, but they can help to speed the rate of recovery and reduce symptoms.

When someone has severe vision loss that persists, even when given steroids, a treatment called plasma exchange (PE) therapy (or intravenous immune globulin) might be used to recover vision. PE therapy is a way of “cleansing the blood” by removing plasma- the liquid part of your blood and replacing it with plasma from a donor or with a plasma substitute. This can help control inflammatory disease symptoms by altering the way that white blood cells work. Certain studies have found that treatment with pulsed intravenous corticosteroids and PE is more effective than the standard treatment of corticosteroids alone.

Treatments for any other health conditions that are causing a neuritis, such as MS, autoimmune disorders or viruses/infections. For example, beta interferons and immunosuppressive drugs may be used to delay or help prevent multiple sclerosis. Some examples of these disease-modifying drugs include: Avonex (interferon beta-1a), Betaseron (interferon beta-1b), Extavia (interferon beta-1b), Plegridy (peginterferon beta-1a), and Rebif (interferon beta-1a).

Vitamin B12 injections are also sometimes given if it’s suspected that vitamin B12 deficiency may be contributing to neuritis (this is considered to be rare).

Prevention

Consult an ophthalmologist and a neurologist so that they can study each case and detect risk factors. Quite often a brain MRI will be done if it is suspected that the patient may have one of the related diseases.